Religion has been part of all societies, but why? A lot of intellectual discourse has tackled the subject, much of it reaching the conclusion that people just need to have gods and so they make them up. But even a quick scan of ancient religious history will show that authentic experience of something awesome — perhaps not “God” or “gods,” perhaps beings with technology so advanced it seemed like magic — inspired the creation and growth of religions around the world.

It was easy for religion to take root, both because authentic experience makes for enthusiastic converts and proselytizers, and because religion indeed fills some human needs. Ancient people expected to deal with the normal troubles of life on their own, but, as Rodney Stark writes in Discovering God, they hoped that the gods would help them with the forces beyond human control:

[P]rimitive peoples … call upon the supernatural for rain, for help in finding game, and for safe voyages. In doing so, they acknowledge the fundamental principle that the supernatural is the only plausible source of many things that human beings greatly desire. Therein lies one key to the universality of religion—its capacity to overcome the generic limitations of human power by invoking entities or forces that transcend nature. Whether it is a Bantu priest in Nigeria chanting that Awwaw grant a good harvest, or a Baptist congregation in Georgia singing, “What a friend we have in Jesus, all our sins and griefs to bear,” religion offers an alternative means to achieve greatly desired ends, when direct methods fail or do not exist.

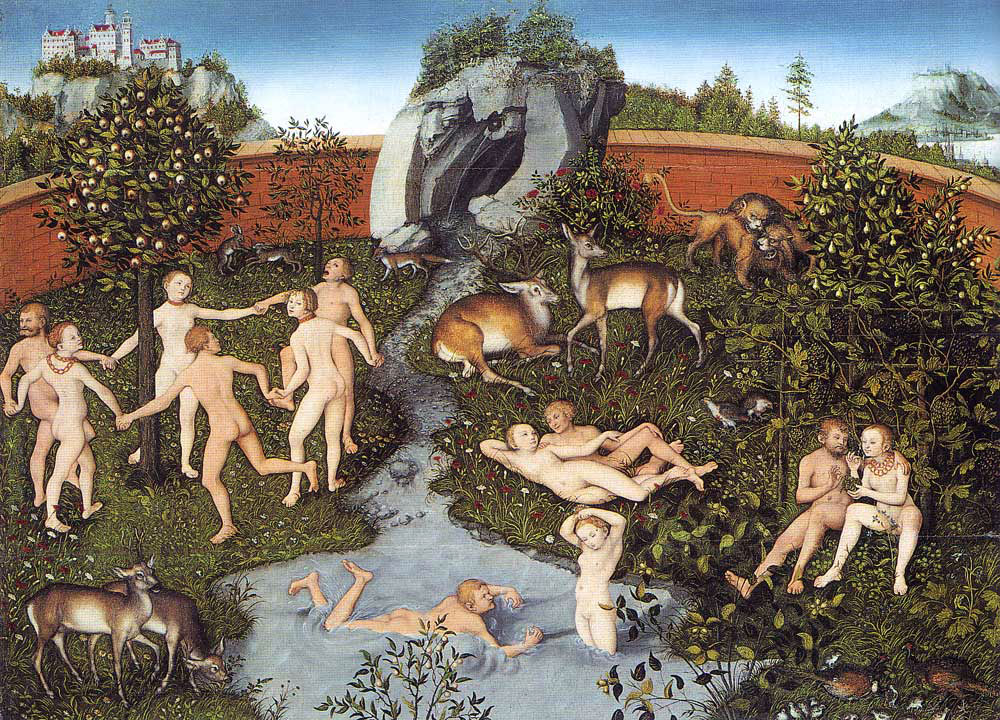

The earliest religions—lost in prehistory and based, perhaps, on real experiences—were more sophisticated than most of the religions they later spawned, and they were more morality-based than later versions. Most stories about gods show them as wrapped up in their own lives, giving little or no thought to the welfare of humanity or individual humans, or to humans’ morality or lack of it. Exceptions are the “bringers of civilization,” divine teachers, deities or demigods whose role is to help, such as Oannes.

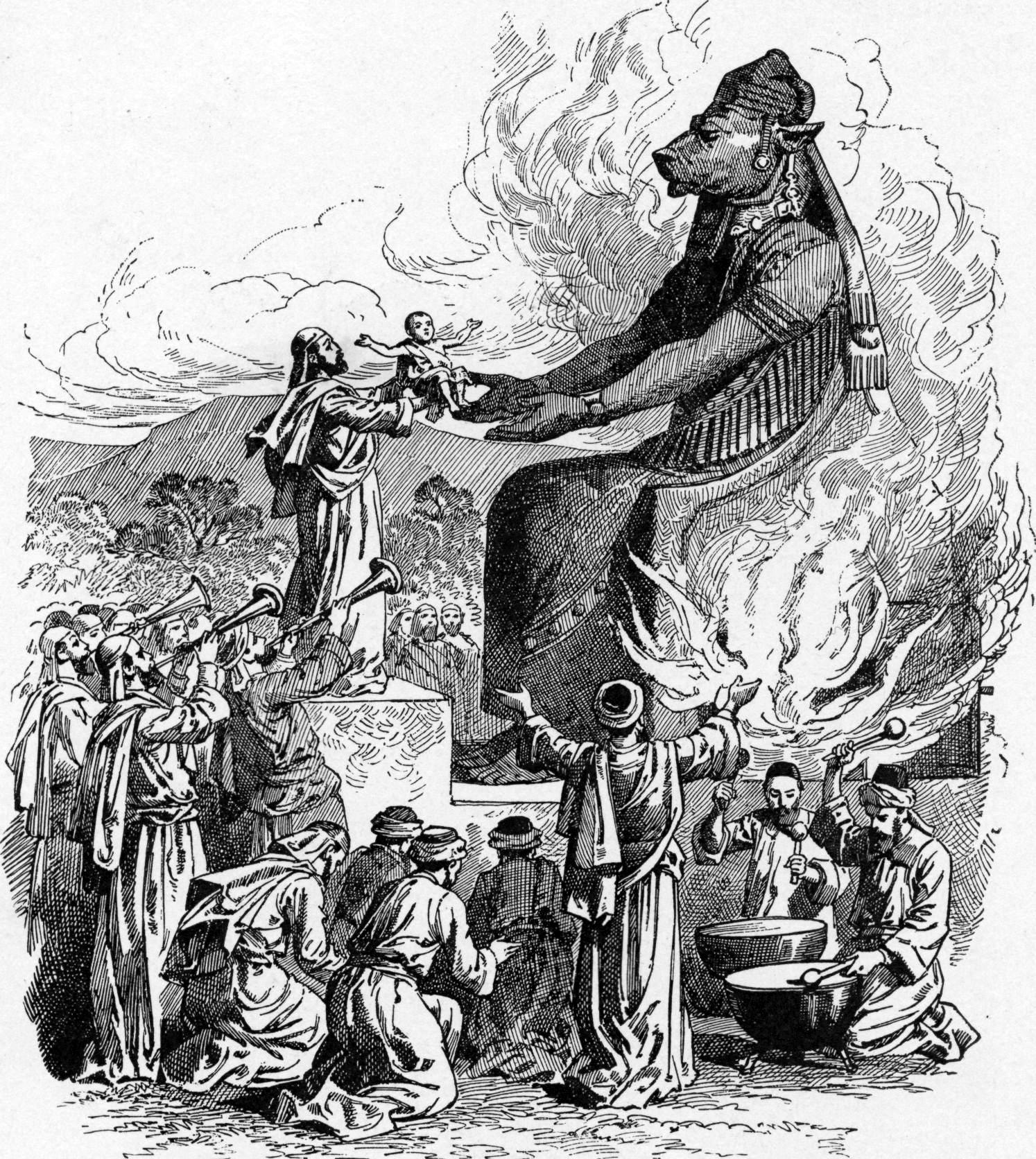

The failure of humans to pay proper tribute to the gods—such as neglecting to make sacrifices—gets attention, but instead of striking deficient humans dead, the gods tend to destroy the whole city (much as a few annoying ants might encourage us to take out a whole anthill).

Gods and goddesses around the world have usually been thought of as a lot like humans, except with superpowers and immortality. They have humanlike needs and desires, and display the whole range of emotions and behaviors, for better and worse. Often, the gods are depicted as human or humanoid forms, with perhaps a pair of wings and eagle head and talons to show they can fly.

Since creation stories of many societies state that humans were made from divine matter—often the blood, spit, or semen of a god or gods — deities that look more or less like us are not necessarily reflecting a lack of imagination on the part of those depicting them; it would be reasonable for ancient gods to look a lot like humans, and in ancient stories, including Bible stories, they are able to pass as human when visiting Earth. Homer writes, “The gods, likening themselves to all kinds of strangers, go in various disguises from city to city, observing the wrongdoing and the righteousness of men.”

Source

But it’s obvious when looking at depictions of gods that the ancients sometimes had a hard time figuring out what they were seeing, or hearing described. “It’s a bird, it’s a plane….” Of course, planes were beyond the understanding of ancient people, as were machines generally. If it moves, it’s a human or other animal. If it flies, it has to be a bird, but, wait, it’s long like a snake, and omigosh it’s breathing fire! If it’s operating a weapon, it must have hands. If it makes loud noise, it must have a mouth.

Descriptions of the gods are often at least partly descriptions of the vehicles in which the gods travel — leading to some odd-looking gods, and perhaps leading to the invention of gods with multiple aspects, avatars—magically transforming from fiery serpent to human form as they step out of or slide off of their fiery serpent, or thunderbird, or silver eagle, or flying elephant.

In another realm from most gods and goddesses is the high god, or creator god, a feature of many ancient religions. The high god creates the universe and/or Earth. In many cases, he or she or they afterwards withdraw into remotest heaven, leaving “down-to-Earth” gods to take on the day-to-day work of running the worldly creation.

Source

Almost without exception, societies that emphasize high-god beliefs feature many gods, who are all subordinate to the high deity. Adherents seemed to find the lesser gods more real, more relevant and accessible compared to the abstract and omnipotent high gods. The monotheist religion of high god Yahweh required that the various gods who were originally in his pantheon be downgraded to divine beings, such as angels and demons, since there could only be one god.

Many scholars believe that the prevalence of high god beliefs is the result not of ancient people around the world making up similar stories, but of essentially the same, authentic, ancient revelations (encounters with “God” or “gods”) being experienced by many primitive cultures globally.

High gods usually are sky deities or sky fathers, ruling over the other gods from the heavens. But many, many other gods are also able to fly, and they put in a lot of time in the sky.

1. Rodney Stark, Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (USA: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008), 38.

Source

Source

Source

Source

source

source

source